Medusa is remembered as a scary woman from Greek mythology who has serpents for hair. She turns anyone who meets her gaze into stone. Yet, beneath the surface of this ancient story lies victim-blaming, othering, and society’s tendency to punish women who survive trauma. When analysed as the act of scapegoating, Medusa’s story becomes a powerful critique of how societies project their guilt and fear onto women who endure what should have broken them. Medusa was a woman condemned for the strength she gained through her suffering.

Medusa had worshiped Athena, but when she needed protection, Athena saw only a younger woman whose beauty threatened her power. Instead of defending her, she cast Medusa out. But the curse was also a weapon. Since no-one would protect her, they would learn to fear her instead.

Scapegoating involves assigning blame to an individual or group to maintain social harmony or deflect attention from larger issues. French philosopher René Girard, who popularised this concept, argued that societies create scapegoats to channel their collective violence and anxiety. This process allows a community to restore order by expelling or punishing the chosen scapegoat.

Medusa’s transformation from a mortal woman into a feared monster exemplifies this dynamic.

Poseidon assaults Medusa in Athena’s temple. But a god is untouchable so instead of punishing him, Athena punishes the mortal girl. She is expendable and now a monster. Medusa becomes a threat to be eliminated so that the world can remain safe for powerful men. Everyone fears her gaze but few ask why she has it.

Medusa’s story mirrors the reality of victim-blaming, where survivors of intimate partner violence are condemned instead of supported. Like Medusa, they are punished for their own trauma, their suffering twisted into shame while the perpetrators remain untouched.

The focus shifts from the actions of the perpetrator to the victim’s body, appearance, or behaviour. This reinforces a culture that restricts women’s behaviour while excusing male transgressions. Medusa’s myth reflects a long-standing tradition of punishing women for circumstances beyond their control. They are branded as threats to the social order when they refuse to remain broken.

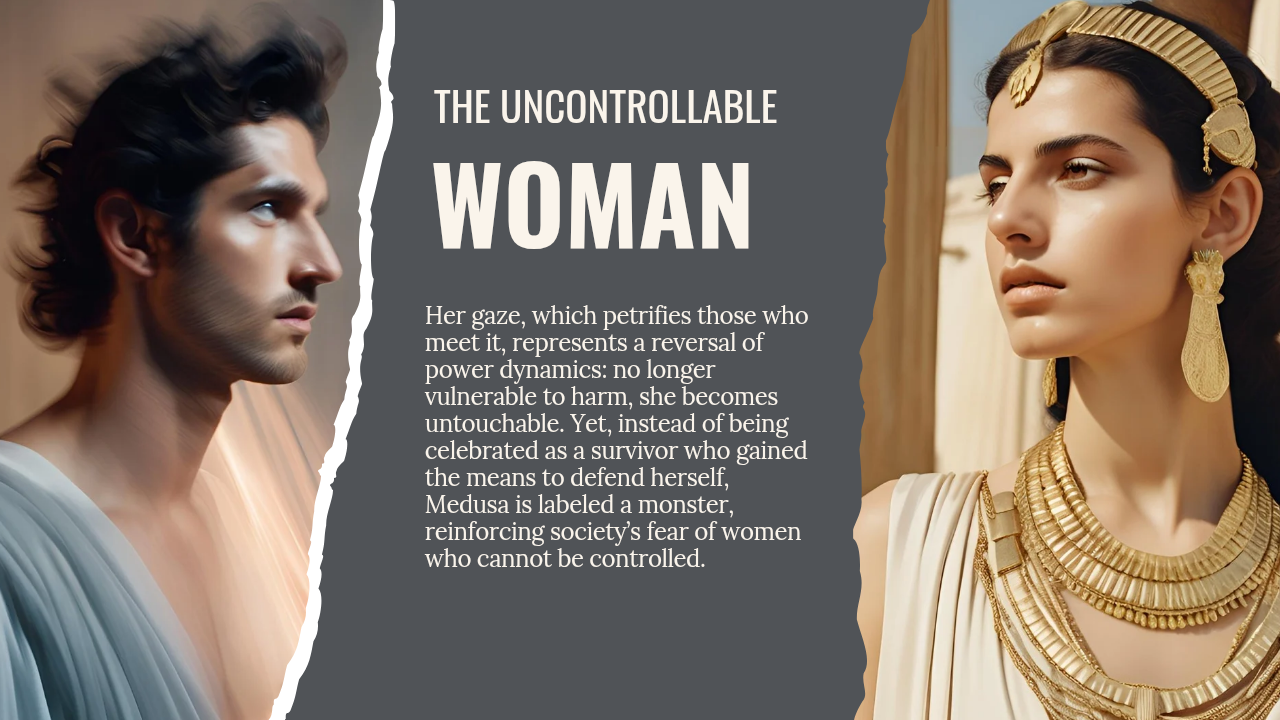

However, Medusa’s transformation can also be seen as a form of empowerment—albeit one born from injustice. Her gaze petrifies those who meet it in a reversal of power dynamics. No longer vulnerable to harm, she becomes untouchable. Yet, instead of being celebrated as a survivor who gained the means to defend herself, Medusa is labeled a monster. From this we understand that society fears women who cannot be controlled.

This fear stems from the threat that such women pose to the status quo, as their autonomy challenges traditional power structures. Thus, the true “curse” is a world that seeks to destroy a woman who dares to exist beyond the limits imposed upon her.

The act of scapegoating Medusa is further evident in her death at the hands of Perseus. Tasked with slaying Medusa as part of his heroic quest, Perseus is celebrated for beheading a woman who had harmed no one unless they sought to harm her first.

By killing Medusa, Perseus restores the patriarchal order, and reaffirms society’s control over female bodies and narratives. His triumph is celebrated as an act of heroism, while Medusa is remembered as a monstrous obstacle to be overcome. This framing erases the injustice of her initial punishment.

Yet, despite this tragic outcome, Medusa’s story has evolved into a symbol of resistance and empowerment in contemporary culture. Feminist interpretations reclaim her image as a representation of female strength, resilience, and defiance against oppression. Her gaze is reimagined as the ability to confront and immobilise those who seek to harm or control her. In this reinterpretation, Medusa challenges the narratives that have historically silenced and demonised women.

The myth of Medusa serves as a timeless allegory of scapegoating. Her story has been reclaimed as a testament to the strength that can emerge from suffering. She reminds us that the real monster is the society that seeks to break her.

5 responses to “Medusa: The Scapegoat of Myth and Society”

Sorry! I did not see your Easter greeting, but bless you too!

Will.

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤️❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Girard has a point, and you are writing on the eve of Palm Sunday. We were exploring this some years ago, though not from a specifically feminist viewpoint, with our late contributor, Austin Mc Cormack , who led us through some of Girard’s insights.

Austin wrote (a short extract from a series of lectures) : For Jesus, non-violence is at the heart of his message, in which we are called to love – even our enemies. This was so threatening to the Roman and Jewish authorities that they eliminated Jesus, hoping his way would die with him.

Austin’s perspective in no way contradicts your insight; brava for your post!

Will!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for the thoughtful commentary, Will. I truly appreciate it because I put a lot of energy into creating a series based on this theme so having the first one be well received means a lot.

Have a Blessed Easter.

LikeLike

keep up the good work!

Will

LikeLiked by 1 person